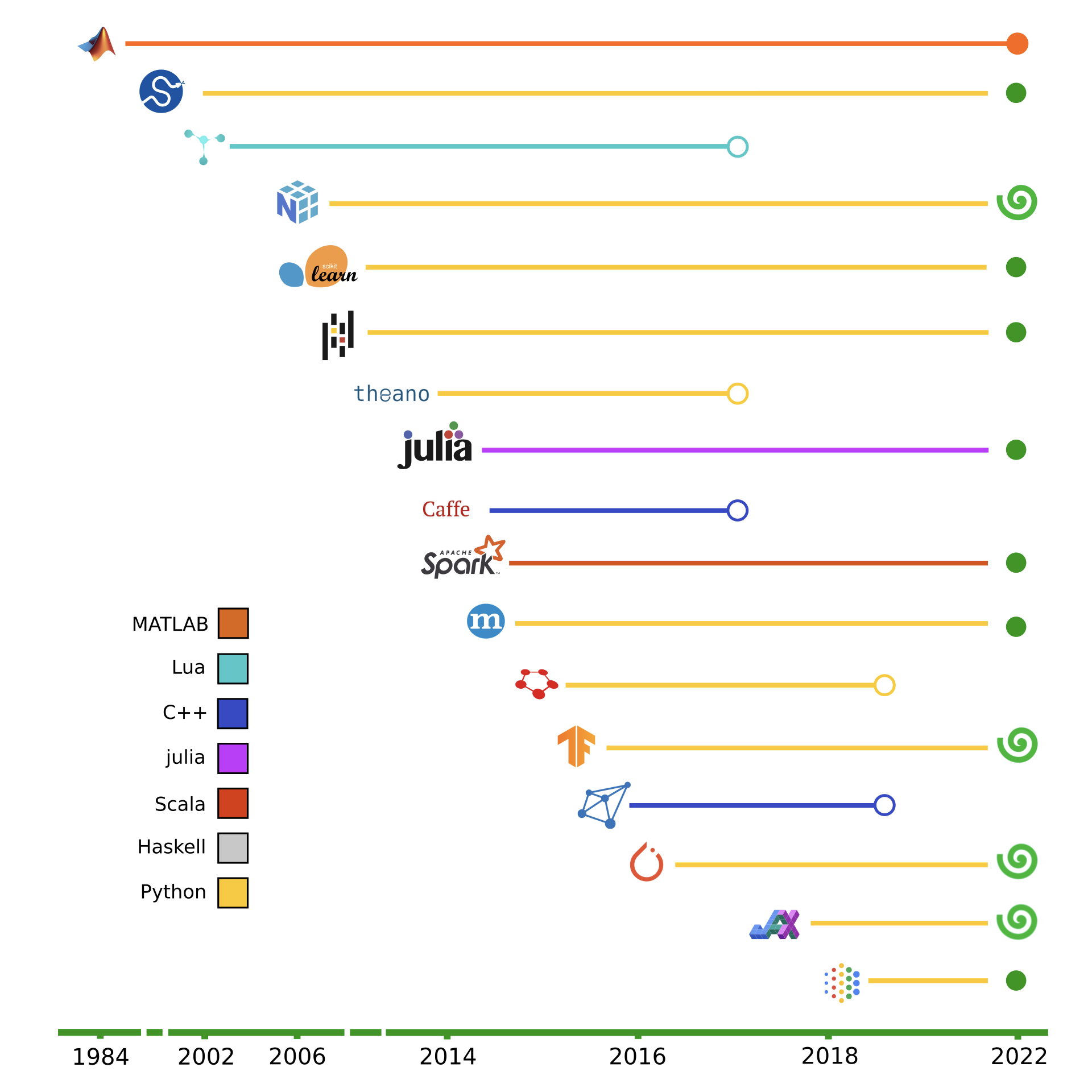

Frameworks#

Here we list some of the most prominent frameworks for array computation. These are the individual frameworks which the wrapper frameworks mentioned above generally wrap around and abstract.

MATLAB  #

#

MATLAB (an abbreviation of MATrix LABoratory) is a proprietary multi-paradigm programming language and numeric computing environment developed by MathWorks, which was first commercially released in 1984. It allows matrix manipulations, plotting of functions and data, implementation of algorithms, creation of user interfaces, and interfacing with programs written in other languages. Although MATLAB is intended primarily for numeric computing, an optional toolbox uses the MuPAD symbolic engine allowing access to symbolic computing abilities. An additional package, Simulink, adds graphical multi-domain simulation and model-based design for dynamic and embedded systems. As of 2020, MATLAB has more than 4 million users worldwide, who come from various backgrounds of engineering, science, and economics.

SciPy  #

#

First released in 2001, SciPy is a Python framework used for scientific computing and technical computing, with modules for optimization, linear algebra, integration, interpolation, special functions, FFT, signal and image processing, ODE solvers and other tasks common in science and engineering. While the user interface is in Python, the backend involves Fortran, Cython, C++, and C for high runtime efficiency. It is built to work with NumPy arrays, and provides many user-friendly and efficient numerical routines, such as routines for numerical integration and optimization.

Torch  #

#

Initially released in 2002, Torch is an open-source machine learning library, a scientific computing framework, and a script language based on the Lua programming language. It provides a wide range of algorithms for deep learning, and uses the scripting language LuaJIT, and an underlying C implementation. It was created in IDIAP at EPFL.

NumPy  #

#

First released in 2005, NumPy is a Python framework which was created by incorporating features of the competing Numarray into Numeric, with extensive modifications. NumPy supports large, multi-dimensional arrays and matrices, along with a large collection of high-level mathematical functions to operate on these arrays. NumPy targets the CPython reference implementation of Python. NumPy addresses the absence of compiler optimization partly by providing multidimensional arrays and functions and operators that operate efficiently on arrays. NumPy arrays are strided views on memory. It has long been the go-to framework for numeric computing in Python.

SciKit Learn  #

#

First released in 2007, Scikit-learn is a Python framework which features various classification, regression, and clustering algorithms including support-vector machines, random forests, gradient boosting, k-means, and DBSCAN, and is designed to interoperate with the Python numerical and scientific libraries NumPy and SciPy.

Theano  #

#

Initially released in 2007, Theano is a Python framework which focuses on manipulating and evaluating mathematical expressions, especially matrix-valued ones, with an inbuilt optimizing compiler. Computations are expressed using a NumPy-esque syntax and are compiled to run efficiently on either CPU or GPU architectures. Notably, it includes an extensible graph framework suitable for the rapid development of custom operators and symbolic optimizations, and it implements an extensible graph transpilation framework. It is now being continued under the name Aesara.

Pandas  #

#

Initially released in 2008, Pandas is a Python framework which focuses on data manipulation and analysis. In particular, it offers data structures and operations for manipulating numerical tables and time series. Key features include: a DataFrame object for data manipulation with integrated indexing, tools for reading and writing data between in-memory data structures and different file formats, and label-based slicing, fancy indexing, and subsetting of large data sets. It is built upon NumPy, and as such the library is highly optimized for performance, with critical code paths written in Cython or C.

Julia  #

#

Initially released in 2012, Julia is a high-level, dynamic programming language. Its features are well suited for numerical analysis and computational science. Distinctive aspects of Julia’s design include a type system with parametric polymorphism in a dynamic programming language; with multiple dispatch as its core programming paradigm. Julia supports concurrent, (composable) parallel and distributed computing (with or without using MPI or the built-in corresponding to “OpenMP-style” threads), and direct calling of C and Fortran libraries without glue code. Julia uses a just-in-time (JIT) compiler that is referred to as “just-ahead-of-time” (JAOT) in the Julia community, as Julia compiles all code (by default) to machine code before running it. Julia is used extensively by researchers at NASA and CERN, and it was selected by the Climate Modeling Alliance as the sole implementation language for their next generation global climate model, to name a few influential users.

Apache Spark MLlib  #

#

Initially released in 2014, Apache Spark is a unified analytics engine for large-scale data processing, implemented in Scala. It provides an interface for programming clusters with implicit data parallelism and fault tolerance. MLlib is a distributed machine-learning framework on top of Spark Core that, due in large part to the distributed memory-based Spark architecture, is very runtime efficient. Many common machine learning and statistical algorithms have been implemented and are shipped with MLlib which simplifies large scale machine learning pipelines. MLlib fits into Spark’s APIs and it also interoperates with NumPy in Python.

Caffe  #

#

Initially released in 2014, Caffe is highly efficient, but is all in C++ which requires frequent re-compiling during development and testing. It was also not very easy to quickly throw prototypes together, with C++ being much less forgiving than Python as a front-facing language. In the last few years, Caffe has been merged into PyTorch.

Chainer  #

#

Initially released in 2015, Chainer is written purely in Python on top of NumPy and CuPy. It is notable for its early adoption of “define-by-run” scheme, as well as its performance on large scale systems. In December 2019, Preferred Networks announced the transition of its development effort from Chainer to PyTorch and it will only provide maintenance patches after releasing v7.

TensorFlow 1  #

#

Initially released in 2015, TensorFlow 1 enabled graphs to be defined as chains of Python functions, but the lack of python classes in the model construction process made the code very non-pythonic. It was hard to create meaningful hierarchical and reusable abstractions. The computation graph was also hard to debug; intermediate values were not accessible in the Python environment, and had to be explicitly extracted from the graph using a tf.session. Overall it was easier to get started on projects and prototype more quickly than in Caffe (the most popular ML framework at the time, written in C++), but it was not much easier to debug than Caffe due to the compiled graph which could not be stepped through. The graph also needed to be fully static, with limited ability for branching in the graph, removing the possibility for pure python control flow to form part of the graph.

MXNet  #

#

Initially released in 2016, MXNet allows users to mix symbolic and imperative programming. At its core, MXNet contains a dynamic dependency scheduler that automatically parallelizes both symbolic and imperative operations on the fly. A graph optimization layer on top of that makes symbolic execution fast and memory efficient. Despite having big industry users such as Amazon, MXNet has not gained significant traction among researchers.

CNTK  #

#

Originally released in 2016, the Microsoft Cognitive Toolkit (CNTK) is an open-source toolkit for commercial-grade distributed deep learning, written entirely in C++. It describes neural networks as a series of computational steps via a directed graph. CNTK allows the user to easily realize and combine popular model types such as feed-forward DNNs, convolutional neural networks (CNNs), and recurrent neural networks (RNNs/LSTMs). CNTK implements stochastic gradient descent (SGD, error backpropagation) learning with automatic differentiation and parallelization across multiple GPUs and servers. It is no longer being actively developed, having succumbed to the increasing popularity of the frameworks using Python frontend interfaces.

PyTorch  #

#

PyTorch came onto the scene another year later in 2016, which also operated very differently to TensorFlow. PyTorch operates based on asynchronous scheduling on the target device, without any pre-compilation of the full computation graph on the target device required. This made it possible to combine asynchronous scheduled efficient kernels with pure Python control flow, and also made it easy to query and monitor the intermediate values in the model, with the boundaries of the “computation graph” having been broken down. This quickly made it very popular for researchers. Generally, PyTorch is the choice of the ML researcher, ML practitioner, and the hobbyist. PyTorch is very Pythonic, very simple to use, very forgiving, and has a tremendous ecosystem built around it. No other framework comes close to having anything like the PyTorch Ecosystem, with a vast collection of third-party libraries in various important topics for ML research.

Flux  #

#

Flux is a library for machine learning geared towards high-performance production pipelines, written entirely in the Julia language. It comes “batteries-included” with many useful tools built in, whilst still enabling the full power of the Julia language to be leveraged. It follows a few key principles. It “does the obvious thing”. Flux has relatively few explicit APIs for features like regularization or embeddings. Instead, writing down the mathematical form will work – and be fast. It is “extensible by default”. Flux is written to be highly extensible and flexible while being performant. Extending Flux is as simple as using custom code as part of the desired model - it is all high-level Julia code. “Performance is key”. Flux integrates with high-performance AD tools such as Zygote.jl for generating fast code. Flux optimizes both CPU and GPU performance. Scaling workloads easily to multiple GPUs can be done with the help of Julia’s GPU tooling and projects like DaggerFlux.jl. It “plays nicely with others”. Flux works well with Julia libraries from data frames and images to differential equation solvers, so it is easy to build complex data processing pipelines that integrate Flux models. Flux and Julia are not used nearly as much as the Python frameworks, but they are growing in popularity.

JAX  #

#

All of the other Python frameworks work well when the aim was “vanilla” first-order optimization of neural networks against a scalar loss function, but are not as flexible when anything more customized is required, including meta learning (learning to learn), higher order loss functions, gradient monitoring, and other important research frontiers involving more customization for the gradients.

These frameworks abstract away most of the gradient computation from the developer, making it hard for them to explicitly track gradients, compute vector gradients such as Jacobians, and/or compute higher order gradients such as Hessians etc.

Initially released in 2018, JAX offers an elegant lightweight fully-functional design, which addresses all of these shortcomings, and uses direct bindings to XLA for running highly performant code on TPUs.

This gives JAX fundamental advantages over PyTorch and TensorFlow in terms of user flexibility, ease of debugging, and user control, but has a higher entry barrier for inexperienced ML users, and despite having fundamental advantages over PyTorch and TensorFlow, it still has a very underdeveloped ecosystem.

JAX is generally the choice of the deeply technical ML researcher, working on deeply customized gradient and optimization schemes, and also the runtime performance fanatic.

JAX is not a framework for beginners, but it offers substantially more control for the people who master it.

You can control how your Jacobians are computed, you can design your own vectorized functions using vmap, and you can make design decisions which ensure you can squeeze out every ounce of performance from your model when running on the TPU.

The ecosystem is evolving but is still in its infancy compared to PyTorch.

As mentioned above, The emergence of libraries such as Haiku and Flax are lowering the entry barrier somewhat.

TensorFlow 2  #

#

With PyTorch showing clear advantages and gaining in popularity in the Python ML community, TensorFlow 2 was released in 2019 which, like PyTorch, also supported eager execution of the computation graph. However, because TensorFlow was not an eager framework by design, the eager-mode was very inefficient compared to compiled mode, and therefore was targeted mainly at ease of debugging, rather than a default mode in which TensorFlow should be run. Without a clear niche, TensorFlow seems to have now focused more on edge and mobile devices, with the introduction of TensorFlow Lite, making it the go-to for industrial enterprise users looking to deploy ML models. Overall, TensorFlow 2 is a mature language which has been around in some form since 2015, has already needed to reinvent itself a couple of times, and one of the main advantages currently is the very strong bindings for edge and mobile devices via TensorFlow Lite. Another advantage is the inertia it has with industrial users who adopted TensorFlow in the past years and haven’t transitioned.

DEX Language  #

#

Since 2020, the creator of PyTorch (and major JAX contributor) Adam Paszke has stopped working much on either PyTorch and JAX, and has been instead spending his time working on the Dex language, which looks to combine the clarity and safety of high-level functional languages with the efficiency and parallelism of low-level numerical languages, avoiding the need to compose primitive bulk-array operations. They propose an explicit nested indexing style that mirrors application of functions to arguments. The goal of the project is to explore: type systems for array programming, mathematical program transformations like differentiation and integration, user-directed compilation to parallel hardware, and interactive and incremental numerical programming and visualization. It is quite early and still in an experimental phase, but this framework would provide hugely significant fundamental improvements over all existing frameworks if it reaches a mature stage of development. The language is built on top of Haskell.